Ruairi Mooney

Artist

From the North Coast to the Canvas: a journey of resilience, daily practice, and the slow discovery of an authentic artistic voice.

When Ruairí Mooney speaks about his work, he does so with the same patience and persistence that shapes his paintings. Recovering from injury, he reflects with quiet gratitude: “I’m lucky in the type of job I have,” he says. “I’m not climbing ladders or on my feet all day. Something like this could really knock you off your stride. I’m hoping that in a week or two I can get back at the easel – even if it’s just from a seated position.”

Before surgery, he had been immersed in a series of commissioned works – bespoke paintings created for people who wanted to capture something deeply personal. “Some are places where people grew up, where they got engaged, or memories of someone who’s passed away,” he explains. “They buy those pieces to hang in their homes for fifty years – something their grandkids will see. It’s a great responsibility, and an honour for them to trust me with it.”

The Geography of Memory

Most of Mooney’s work begins along the North Coast – the place he knows best – but commissions have pulled him in unexpected directions.

“I’ve had lovely requests from Murlough Beach down near Newcastle, parts of the Antrim Coast, even Sligo – around Ben Bulben” he says. “They’re places I might not have thought to paint myself, but they’ve given me the chance to see new landscapes and try something fresh.”

Each commission brings its own dialogue. “Sometimes people are very specific – they’ll want the view from their holiday home, the exact angle they look out from in the morning. I did a piece of West Strand Beach in Portrush for someone who grew up there. They wanted their family apartment included, the colourful one in the row overlooking the bay. It meant something to them – and that becomes part of the painting.”

Other clients hand over full creative control. “You get people who just trust the process,” he says. “They don’t know exactly what they want, but they’ll know it when they see it. I love that kind of freedom.”

Commissions and Creative Flow

Revisiting familiar places has made Mooney increasingly aware of perspective. “There’s a fair bit of that,” he says. “Someone might see a painting in an exhibition and say they love everything about it except one small thing – maybe they want it turned slightly or brought in closer to show a certain feature. I like that. They get a say in the creative process, and I know they’re getting exactly what they want.”

Between commissions, he builds original collections guided by instinct.

“I just start with whatever idea I’m drawn to,” he explains. “After two or three pieces, a trend starts to appear – maybe in colour palette or subject matter. It’s like a musician making an album: each song stands alone, but they share a tone or a mood. I don’t plan it; I discover it.”

That spontaneity coexists with pragmatism. “If I wasn’t careful, I’d paint Portstewart Strand every day,” he laughs. “It’s about balance – what I’m drawn to versus what people respond to. Every artist would love to paint purely for themselves, but you have to be realistic too. You can’t ignore what people love.”

The Social Media Paradox

For Mooney, social media is both a tool and a trap. “If you’re in a creative block, Instagram is probably the worst place you could be,” he says. “You end up with productivity guilt – seeing other artists posting new work every day and wondering why you didn’t think of that. You start subconsciously copying what isn’t yours.”

He believes real inspiration comes from physical spaces.

“Go to a gallery,” he says. “Look at paintings on a blank wall, without likes or comments swaying you. Decide if you like it for yourself. Online, you see what pleases the masses. It’s fast, surface-level – people scroll past in seconds. If I spend forty hours on a painting, someone might look at it for three seconds.”

Still, he acknowledges the reach it gives. “Social media is brilliant for connecting with people and getting your name out there,” he admits. “But for genuine appreciation of art, nothing beats seeing it in person.”

Community and Encouragement

Exhibiting has deepened that appreciation. “I’ve had great support from other artists who come to shows,” he says. “Sometimes they just want to see what’s happening; sometimes it gives them the nudge to do their own exhibition. Even if it’s just learning how to get started – how to plan it, organise it. That side of things can be just as encouraging.”

Mooney values that sense of creative momentum – how one artist’s work can quietly give another permission to try. “I’ve done the same myself,” he admits. “You go to someone else’s show, and it gets you thinking again.”

From the Pitch to the Canvas

Before landscapes, Mooney’s early paintings were rooted in sport and portraits of athletes “At the start, I found it hard to take myself seriously as an artist,” he says. “It’s only in the last year that I’ve been able to say, ‘I’m an artist,’ without it sticking in my throat. People knew me for Gaelic football, not painting. So sports felt like a safer place to start.”

That decision turned out to be formative. “Those commissions helped me build confidence. I knew the subject matter so well that I didn’t feel like an imposter,” he recalls. “It gave me time to get familiar with paint, colour, and process – the kind of fluency you only earn through hours of repetition.”

Learning the Language of Paint

Mooney compares those years to a crash course in learning a new instrument. “I studied art at school and trained as a teacher, but it wasn’t until lockdown, during my ‘100 Days of Art’ fundraiser, that I really got to know paint,” he says. “I was painting every day, and you build this fluency – not just in colour theory but in confidence.”

Raising funds for the mental health charity Aware NI, what began as a way to stay creative during isolation quickly became something larger: a community effort that connected his art practice to purpose. By the end of the project, he had raised over £1,000 for the charity.

He laughs, recalling how tentative he once was. “I used to be scared to waste paint, scared to go over the lines, scared to ruin something. But eventually you realise – you can’t really do it wrong. You get braver. You start slapping paint on with brushes, palette knives, anything.”

That willingness to experiment has become central to his work. “I love practice,” he says. “That’s why I connect painting with sport or even music – the idea of gradual improvement, challenging yourself, growing. You can’t help but get better. You find your voice by doing.”

Discipline and Belief

His time on the Gaelic pitch taught him lessons he now carries into the studio.

“I wasn’t naturally gifted,” he says. “I was a grinder, a late bloomer. That’s why I don’t really believe in talent – it’s repetition, practice, and hard work. But when you love what you’re doing, that hard work doesn’t feel hard.”

He’s logged thousands of hours with a paintbrush in hand. “I’m not an expert,” he says, “but I’ve definitely put the hours in. I can stand over my work now and say it’s authentic. It’s not trying to be something it’s not.”

Colour, Light, and Geometry

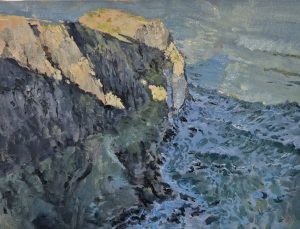

Mooney’s paintings are known for their sense of light – the gleam of sun cresting over a hill, or the shimmer of white along a wave. But there’s another element that has become distinctively his: geometric shapes scattered through the composition.

“When I moved from sport to landscapes, it didn’t feel natural at first,” he admits. “It was like wearing boots that didn’t quite fit. I’d see other artists painting the same beaches and landmarks, and I didn’t want to just add another version. I wanted to do it differently – to make it mine.”

That urge led to experimentation: lines, reduced palettes, blocks of colour. “Those squares and bars weren’t a planned decision,” he says. “I was just experimenting. When I look back now, those early pieces feel raw – maybe even naïve – but there’s a freshness in that. You only get that when you’re trying something for the first time.”

The shapes still appear in his work, though more sparingly. “I like that people recognise them,” he says. “They’ve become part of my language – a way of introducing tones and energy that might not fit otherwise. They’re visible, but not distracting. It’s just something that naturally grew out of the process.”

The Ongoing Search for Authenticity

For Mooney, painting is a constant negotiation between curiosity and control – an ongoing search for authenticity. “I was talking to a teammate recently about originality,” he says. “I don’t think I’ve found my true, original style yet – or the perfect piece that sums me up. But every time you paint, you get one step closer. You’re peeling back layers, chipping through to the next surface, trying to reach the core.”

That pursuit is what keeps him excited. “I could talk about creativity and process all day,” he says. “I want to reach that piece that feels like me – the one people look at and say, ‘That’s Ruairí Mooney.’ I don’t know when it’ll happen. Maybe in five years, maybe twenty-five. But that’s the beauty of it – you never really arrive. You’re always getting closer.”

Find out more information about Ruairi’s latest work, along with prints and commissions via his website: artbymooney.com

Keep up with Ruairi on social media: @artbymooney

Support Go Leor. Get the Print. Join the Story.

Go Leor is an independent Irish arts magazine built by hand, heart, and community. Your support keeps meaningful storytelling alive – in print, in culture, and in conversation. Through Patreon, you can join as a monthly supporter and receive exclusive benefits across our tiered memberships:

Fir Bolg: Your name printed inside every issue.

Muintir Neimhidh: Your name + monthly issue delivered (UK & Ireland) and PDF issues.

Muintir Partholóin: All previous benefits + monthly editor’s dispatch.

Bradán Feasa: All benefits + help shape future articles and themes.

Your backing helps us print, publish, and grow a space for creative voices across Ireland and beyond.

The Latest Articles

Frances Magee – Preserving Ireland’s Natural World in Cyanotype Magic

In her North Belfast garden, Frances Magee transforms carefully tended plants into luminous cyanotypes – where texture, imperfection and light combine in work that feels timeless.

Mark Bonello – Capturing the Spirit of Ireland’s North Coast

From London galleries to the North Coast studio, Mark Bonello paints light, labour, and lived experience with unwavering focus

From Donegal to Belfast – Katriona Sweeney’s Authentic Irish Design

Where Irish memory, bold typography, and hand-painted craft converge – from Donegal buses and rush crosses to Belfast walls and wearable design.

Anthony Murphy and the Secrets of Ancient Ireland

An astronomer’s path into Ireland’s ancient past – tracing how skywatching, myth and archaeology converge across the island’s landscapes.

Desima-Jayne Connolly on Building Arts Centres Around People and Place

From Christmas markets to the return of light, how collaborative programming at Flowerfield and Roe Valley places people, place and wellbeing at the centre of cultural life.

Fight Like a Girl: Ana Fish on Safer Spaces & Murals

Tracing a life shaped by movement, myth, and community – using street art to reclaim space, tell shared stories, and make the everyday world feel safer, softer, and more alive.