Bob Speers

Artist

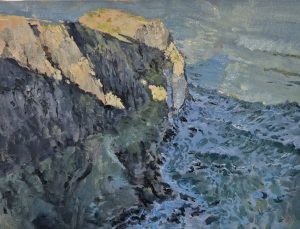

In a room filled with timber, peat, and light, artworks hung on walls are more like fragments of the land itself – weathered, breathing, and alive with memory.

Inside the gallery, walls are filled with textures of peat and cloth, framed in salvaged timber. Bob Speers’s work feels both ancient and immediate – paintings that seem to breathe the land itself.

His long-time collaborator Colin Agnew moves quietly among the pieces, preparing for their next showing.

“It officially opens on the 13th,” he says. “Professor Jonathan Pilcher from Queen’s University is coming down to talk about the evolution of bogland and the environmental issues surrounding it.”

Each piece carries its own story. One canvas was inspired by Garry Bog, another by Speers’s childhood haunts in County Antrim.

“Bob sees it as a kind of portal,” Agnew says, “a perspective drawn by the light coming through.”

Thin Spaces

At the heart of Speers’s practice lies the idea of the thin place – a landscape where the veil between the physical and the transcendent feels porous. Peatlands, or bogs, embody this liminal quality: places where the material and the numinous touch.

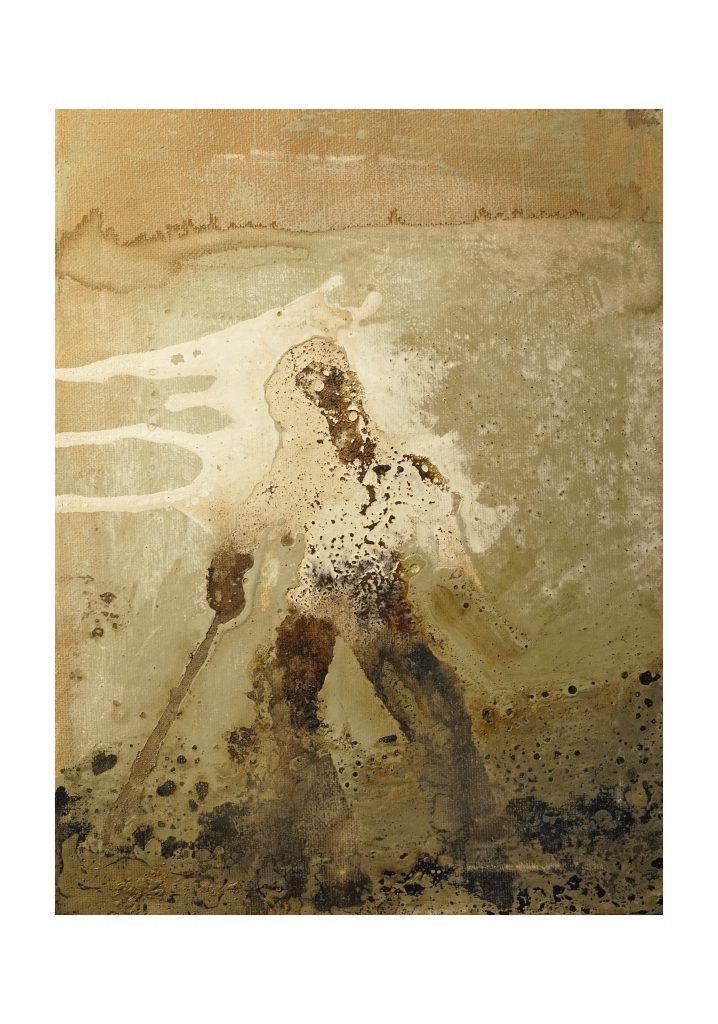

Each canvas hums between those worlds – dense with earth, alive with light. As Speers says, “My art is currently informed by habitual wanderings through different levels of moor and bog.”

This is the guiding principle behind his exhibition Thin Place: to explore that moment of connection when the land seems to shimmer with both presence and absence – a “mystical space,” he explains, “where the boundary between our tangible world and the unseen world seem to touch.”

Material Memory

Speers practises two intertwined disciplines: fine art and songwriting. His visual work evolved from figurative painting in the 1970s into a land-based, meditative practice that merges process and pilgrimage.

“I collect a sample from each bog I visit,” he says. “So that, in essence, the bog named is to be found in the painting.”

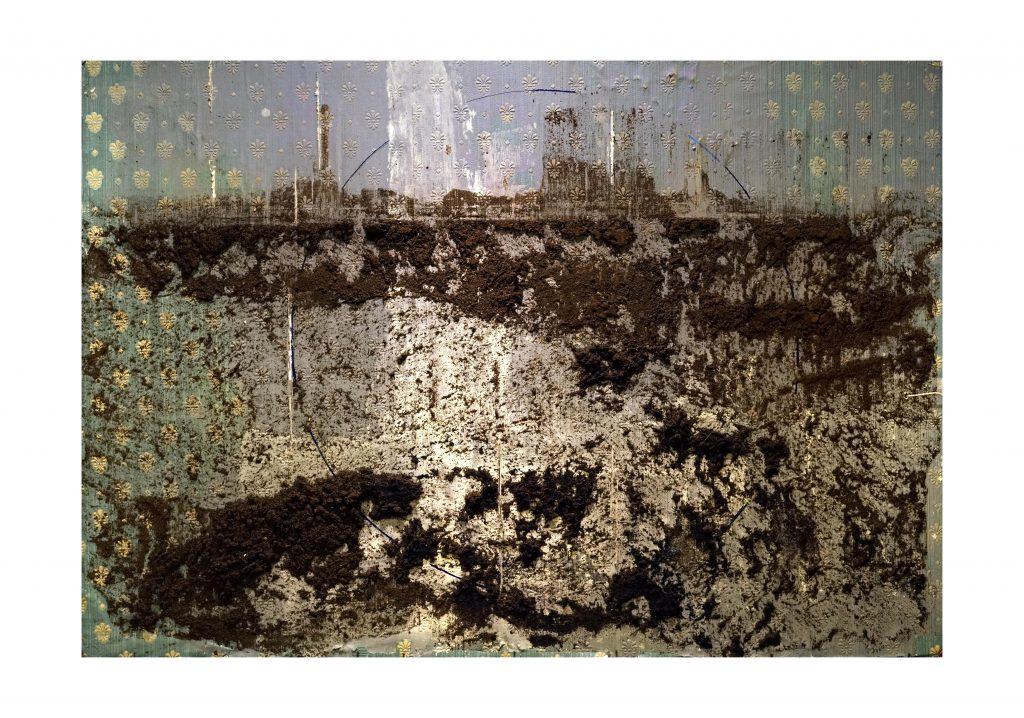

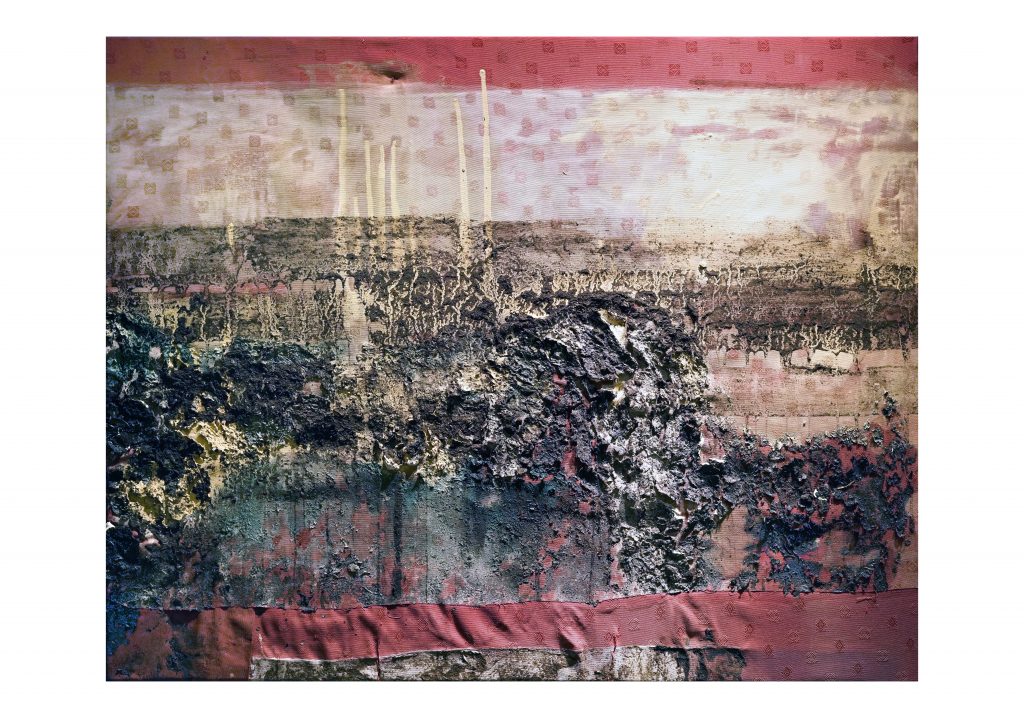

Those samples – peat, clay, water, and moss – are mixed with oils, acrylics, commercial matte paints, and discarded domestic fabrics: sheeting, wallpaper, even old clothing.

“It’s all stuff most people would throw away,” Agnew says. “Old timber, bits of fabric. That’s part of the point – environmental, cyclical, nothing wasted.”

The surfaces that emerge are tactile and weathered – marked by the subtle colours, lines, and incisions of land that has lived through centuries of human and elemental change.

As one gallery visitor once put it, “Bob Speers has a perspective on the land which is often overlooked.”

The Language of Colour

Speers’s paintings exist within the Irish landscape tradition but adopt a contemporary, metaphysical approach. “The colour’s there in the landscape,” he says. “It’s the light, the air, the silence.”

His long-standing interest in earth, peat-bog, and hinterland focuses on what he calls “the human and weathering imprint.”

Each work attempts to evoke “an equivalent atmosphere to that of the actual terrain” – a balance of beauty, decay, and transcendence.

Wallpaper fragments often reappear beneath the surface as a quiet metaphor for repetition and memory – “how things repeat and change over long periods.”

In collaboration with Professor Pilcher, Speers once examined a 10,000-year-old peat core. “He handed me a piece,” Speers recalls, “and when I opened it, it was just new. That gives you a strange feeling.”

A Magical Ecology

For Speers and Agnew, bogs are living archives.

“Every time we visit one, something magical happens,” says Agnew, a horticulturalist by trade and former supervisor of Belfast’s Botanic Gardens.

“That’s why this exhibition is called Thin Place – the bog really is a magical space where something unseen always seems to be present.”

Speers’s environmental concern runs through his practice. The use of organic material reflects his interest in habitat preservation – peatlands as both sacred and threatened ground.

One painting even hints at distant smokestacks on the horizon: “That’s an industrial scene,” Agnew notes, “a factory poisoning the earth.” Speers adds quietly, “That was in County Meath, supposed to be rewilded – but the machines were still there, right when I picked up a sample for my work.”

Each painting becomes both record and resistance – a way to keep the land alive through art.Speers has seen first-hand how many of Ireland’s bogs, once slated for protection or rewilding, continue to be cut and degraded through lax oversight and uneven policy. At sites supposedly under conservation, he’s encountered heavy machinery and commercial extraction still at work – a quiet erasure happening in plain sight.

Returning to Paint

Although deeply rooted in landscape, Speers’s path began in music. He first exhibited with the Royal Ulster Academy in the 1970s but spent much of the following decades writing and performing songs across Ireland, Britain, and Canada.

His acclaimed album Northland (1990) drew directly from the Antrim coastline – a lyrical parallel to his later visual work.

When he returned to painting years later, Agnew remembers recognising the shift immediately. “He said, ‘I’ve started to paint again,’ and showed me a small canvas. I knew straight away he’d been to the bog – the colours gave it away.”

Since then, Speers’s exhibitions have spanned Belfast, Dublin, Portstewart, and Ballymena. At the National Botanic Gardens, a staff member remarked that it was “the best artwork seen in the gallery in 25 years.”

The Murder of Crows

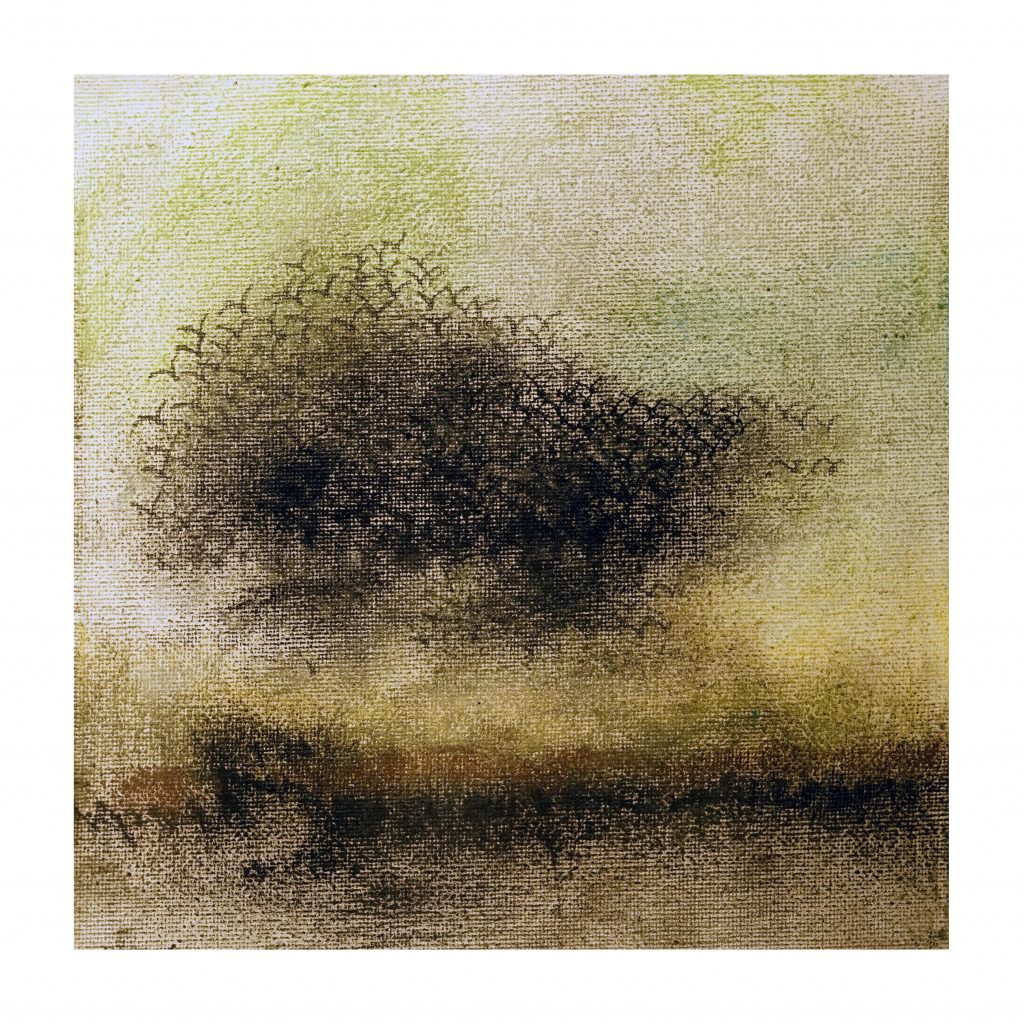

Amid the creative chaos of Speers’s Rathkenny studio, one painting stands apart – Murder of Crows.

“That was just lying around,” Agnew says. “A throwaway. But it’s beautiful.”

Speers smiles. “I was out one day, the wind blowing through the trees, and there was this multitude of crows. They call it a murder. I’ve never forgotten it.”

The piece captures the rhythm of flight and the pulse of weather – the same sensibility that runs through his songs.

Sound and Soil

Music remains inseparable from his visual work. “He’s so in tune with nature,” says Agnew. “I don’t know any Irish artist who does it quite like Bobby.”

He recalls one summer walk through Dundonald Bog: “We were talking about how we never hear curlews anymore. I asked him to give a curlew call – and he did. Within seconds, curlews appeared overhead, circling us. Five of them. It was like magic.”

Speers nods. “That was a rare thing,” he says. “Maybe it was their first flight.”

Legacy and Continuity

Speers’s art, like his music, lives between sound and silence, surface and depth.

It belongs to the Irish landscape tradition yet reaches toward something metaphysical – “a sense of transcendence,” he says, “created by the unique combination of light, air, and silence in these largely unexplored but intriguing places.”

As Agnew puts it, “He doesn’t just paint the bog. He listens to it.”

And somewhere between sound and soil – in those rare thin places where worlds touch – Bob Speers continues to translate the land: one canvas, one song, one moment of quiet magic at a time.

Book your FREE tickets for Thin Place – Bob Speers and Jonathon Pilcher in Conversation, Thursday 13th November, Mid-Antrim Museum and Arts Centre at The Braid: thebraid.ticketsolve.com

Find out more about Bob Speers and his work via his website: bobspeers.co.uk

Support Go Leor. Get the Print. Join the Story.

Go Leor is an independent Irish arts magazine built by hand, heart, and community. Your support keeps meaningful storytelling alive – in print, in culture, and in conversation. Through Patreon, you can join as a monthly supporter and receive exclusive benefits across our tiered memberships:

Fir Bolg: Your name printed inside every issue.

Muintir Neimhidh: Your name + monthly issue delivered (UK & Ireland) and PDF issues.

Muintir Partholóin: All previous benefits + monthly editor’s dispatch.

Bradán Feasa: All benefits + help shape future articles and themes.

Your backing helps us print, publish, and grow a space for creative voices across Ireland and beyond.

The Latest Articles

Frances Magee – Preserving Ireland’s Natural World in Cyanotype Magic

In her North Belfast garden, Frances Magee transforms carefully tended plants into luminous cyanotypes – where texture, imperfection and light combine in work that feels timeless.

Mark Bonello – Capturing the Spirit of Ireland’s North Coast

From London galleries to the North Coast studio, Mark Bonello paints light, labour, and lived experience with unwavering focus

From Donegal to Belfast – Katriona Sweeney’s Authentic Irish Design

Where Irish memory, bold typography, and hand-painted craft converge – from Donegal buses and rush crosses to Belfast walls and wearable design.

Anthony Murphy and the Secrets of Ancient Ireland

An astronomer’s path into Ireland’s ancient past – tracing how skywatching, myth and archaeology converge across the island’s landscapes.

Desima-Jayne Connolly on Building Arts Centres Around People and Place

From Christmas markets to the return of light, how collaborative programming at Flowerfield and Roe Valley places people, place and wellbeing at the centre of cultural life.

Fight Like a Girl: Ana Fish on Safer Spaces & Murals

Tracing a life shaped by movement, myth, and community – using street art to reclaim space, tell shared stories, and make the everyday world feel safer, softer, and more alive.