Ana Fish

Artist

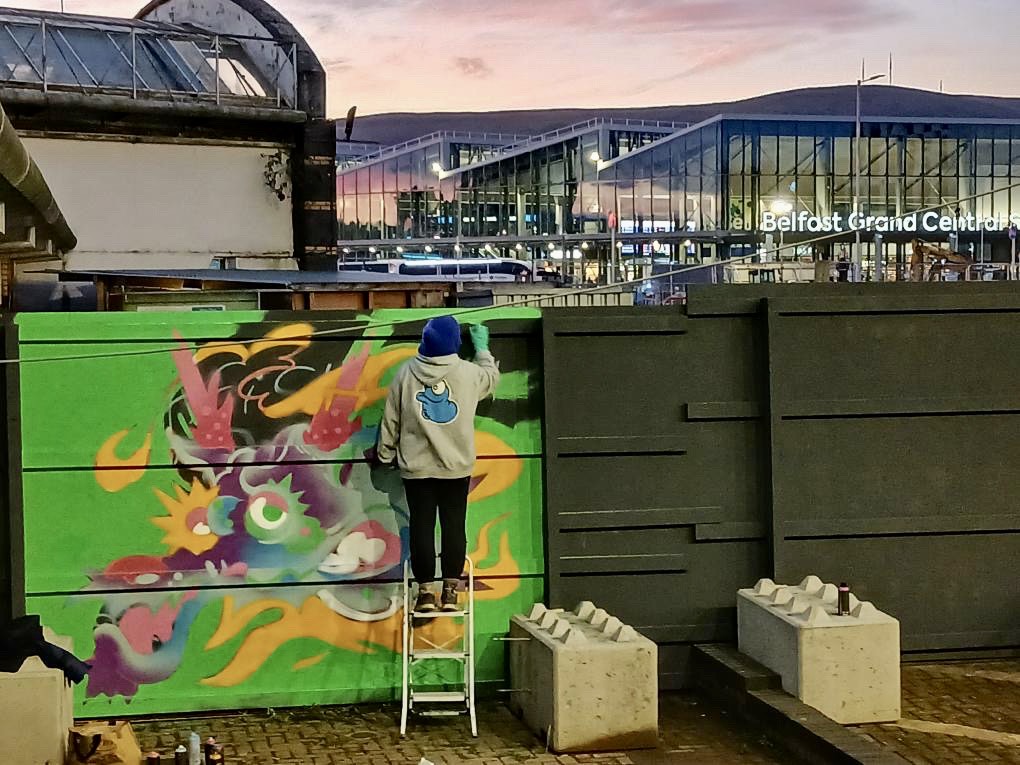

Tracing a life shaped by movement, myth, and community – using street art to reclaim space, tell shared stories, and make the everyday world feel safer, softer, and more alive.

There is a particular openness that runs through Ana Fish’s work – a sense that the figures she paints are not just occupying walls, but actively reclaiming them. That openness mirrors her own path. Born and raised in Russia, Ana moved to the UK at just 17, carrying little more than her sketchbooks, curiosity, and a willingness to figure things out as she went. It was a leap that shaped not only her creative life, but how she understands freedom, community, and what art can do in public space.

Now based in Belfast, Ana balances her mural practice with work in the health service at Ulster Hospital, where she works as a maternity support worker on the labour ward. It is demanding, grounded work – intensely human, physically and emotionally present. That grounding seems to feed directly into her art. There is empathy in her murals, an awareness of bodies, vulnerability, strength, and care that feels lived rather than theoretical.

Leaving Russia at Seventeen

Ana’s move from Russia to England was decisive and formative. Offered a place at Arts University Bournemouth to study animation, she left home young and never truly returned to live there. Her family remains in Russia, and she stays in touch, but her adult life – learning how systems work, how to survive independently, how to be herself – unfolded elsewhere.

The UK became not just a place to study, but a place where she could breathe more freely. That sense of displacement, of being between cultures, echoes subtly through her work – figures that feel mythic yet contemporary, familiar yet slightly uncanny, shaped by multiple visual traditions.

Her background in animation still surfaces clearly. She trained as a 2D animator, working with frame-by-frame movement, illustration, and early commissions before murals entered the picture. Winter months, when outdoor painting slows, often pull her back into that illustrator’s mindset – sketching, stitching, experimenting, rug tufting, and making work simply for the pleasure of it. It is a reminder of why she chose a creative life in the first place.

Street Art as a Way of Belonging

Spray paint, for Ana, began almost accidentally. She tried it on a whim and found she loved the physical act of it – the movement, the immediacy, the scale. But more than the medium itself, it was the people that drew her in.

As an immigrant, she speaks about how the street art community became the first place she truly felt she had “found her people.” Festivals, travel, painting outdoors, meeting artists from wildly different backgrounds – all of it formed a social fabric that felt welcoming, down-to-earth, and refreshingly unpretentious.

She describes street art as inherently accessible. Unlike galleries, it doesn’t ask permission. It doesn’t demand prior knowledge. It appears in neighbourhoods, invites conversation, and draws in people who might never step into a formal art space. Passersby stop, ask questions, offer opinions. Art becomes part of daily life rather than something removed from it.

That social element is not an add-on to her practice – it is central. Painting, for Ana, is inseparable from travel, friendship, shared meals, late nights, and long conversations. The work is made alongside life, not in isolation from it.

Kingston and Taking Space Back

One of the clearest examples of how Ana thinks about place came through her mural for the Kingston Mural Festival. Before she even arrived, organisers Sky High and Roo spoke to her about the area she would be painting in – a location previously ranked as unsafe for women and children.

Murals, had already begun to change that perception. Colour, presence, and visibility were shifting how people moved through the space and how welcome they felt there. For Ana, that context mattered deeply.

Her response was a Valkyrie – a figure drawn from mythology, powerful and watchful – accompanied by the words “Fight Like a Girl.” The phrase is confrontational, reclaiming a term often used dismissively and turning it into a statement of pride and resistance.

The mural was not about decoration. It was about empowerment. About women taking space back. About visibility as a form of safety. Ana speaks about wanting to accentuate that transformation, to honour how street art can actively influence daily life rather than simply reflect it.

Themes of feminism, queerness, and mental health run consistently through her work. They are rarely heavy-handed. Her figures are cartoon-inflected, colourful, and inviting – a deliberate choice that makes difficult ideas more digestible, more approachable. The message is there, but it meets people where they are.

Waterford, Friendship, and Norse Myth

That sense of shared experience was equally present when Ana travelled to Waterford with her friend Constance for Waterford Walls. Together, they painted Freya and Loki – two figures from Norse mythology brought into conversation on the wall.

Ana often documents these trips, not just the finished murals but the process around them – the travel, the laughter, the moments between layers of paint. There is something deeply human in seeing an artist enjoy their own work, especially in a field where burnout and isolation are common.

Freya and Loki, like many of Ana’s figures, carry layered meanings. Strength and trickery. Femininity and disruption. Old myths refracted through contemporary concerns. Painted far from their original cultural contexts, they become tools for connection rather than relics.

Armenia and Choosing Gentleness

Ana’s sensitivity to place became even more pronounced during her time painting in Armenia with Femstreet as part of Dili Fest. Armenia, she notes, does not yet have a strong tradition of street art, and public murals can feel confronting in a more conservative cultural landscape.

Rather than impose her usual figurative style, she chose to depict blue rock thrushes – birds native to the region. The decision was both practical and poetic. Drawing from nature offered a gentler entry point, something immediately recognisable and less likely to alarm or alienate.

There was also a personal layer. Ana references a Soviet-era film, Blue Bird, which she watched growing up – a story that framed the bird as a symbol of happiness. Painting stylised thrushes in a mountainous nature reserve allowed her to weave together childhood memory, local ecology, and cultural sensitivity.

It is a quiet example of her broader approach – listening first, responding thoughtfully, and understanding that not every wall calls for the same kind of voice.

Working With What the Wall Gives You

Ana speaks passionately about surfaces. Smooth walls. Damaged walls. Lamp posts, panels, odd architectural interruptions. Rather than fight against them, she tries to incorporate them into the work.

A lantern becomes a glowing star. A curve suggests movement. A car becomes a three-dimensional canvas that wraps the image around itself.

This attention to context is part of what gives her murals their cohesion. They feel embedded rather than imposed, shaped by the urban fabric they sit within.

Looking Ahead to Belfast and Beyond

Looking forward, Ana is excited for Hit the North in 2026. The Belfast-based festival holds particular significance for her. It is local, social, and deeply rooted in the city she now calls home.

She speaks about the joy of welcoming visiting artists, introducing them to Belfast, and watching them connect with the place. For her, Hit the North has one of the strongest social dynamics of any festival she has attended – artists meeting artists, conversations extending long after the paint dries.

Whether working on small walls or large ones, Ana measures progress not by scale but by growth. Is this mural better than the one six months ago? Does it say something more clearly? Does it feel truer?

Painting as a Way of Living

Ana Fish’s practice resists neat categorisation. It is animation-informed but rooted in street culture. Politically aware but visually inviting. Social by necessity rather than design.

Her murals suggest that art does not have to shout to be powerful. Sometimes it simply needs to show up, take space, and invite people to feel a little safer, a little more seen, as they pass by.

That philosophy – attentive, generous, quietly defiant – runs through everything she makes.

Keep up with Ana via her social media: @ana.fish.art

Support Go Leor. Get the Print. Join the Story.

Go Leor is an independent Irish arts magazine built by hand, heart, and community. Your support keeps meaningful storytelling alive – in print, in culture, and in conversation. Through Patreon, you can join as a monthly supporter and receive exclusive benefits across our tiered memberships:

Fir Bolg: Your name printed inside every issue.

Muintir Neimhidh: Your name + monthly issue delivered (UK & Ireland) and PDF issues.

Muintir Partholóin: All previous benefits + monthly editor’s dispatch.

Bradán Feasa: All benefits + help shape future articles and themes.

Your backing helps us print, publish, and grow a space for creative voices across Ireland and beyond.

The Latest Articles

Desima-Jayne Connolly on Building Arts Centres Around People and Place

From Christmas markets to the return of light, how collaborative programming at Flowerfield and Roe Valley places people, place and wellbeing at the centre of cultural life.

Finding Magic Stillness in the City: Joel Simon’s Paintings

Scenes observed slowly and held with care, where light, posture, and silence allow the ordinary street to become a quiet stage for feeling

Inni-K on Still A Day: Genuine Irish Songwriting

In the aftermath of touring Still A Day, the singer, composer, and multi-instrumentalist considers music, nature, and what remains once the movement stops.

Bob Speers and the Quiet Magic of Ireland’s Bogs

In a room filled with timber, peat, and light, artworks hung on walls are more like fragments of the land itself – weathered, breathing, and alive with memory.

Hernan Farias on Light, Connection and Creative Growth

From the Classroom to the Camera – charting his shift from teaching English in Chile to full-time photography in Northern Ireland.

The Colour & Spirit of Time: Tricia Kelly’s Journey with Ócar

Exploring how sixty million years of volcanic fire, weather, and transformation created the red ochre that now colours Tricia’s life and work.