Roberta Bacic

Conflict Textiles Curator

Roberta Bacic reflects on decades of curating stories through fabric, the responsibility of memory, and the importance of empowering future generations to continue communicating beyond words.

“Well, my role has been changing and expanding over the years. In a way. I started in 1975 to collect a few Arpilleras in solidarity with the women who were telling their stories. And the stories were not going out from Chile.”

So begins Roberta Bacic, curator of Conflict Textiles, whose life’s work has been shaped by the powerful handmade textiles known as Arpilleras. Experiencing the turmoil of Chile’s military dictatorship, these textiles became a visual voice for women silenced by repression.

“So it’s not that there was a tradition in Arpilleras. They were born out of the need to express themselves,” Bacic says. “Especially because in traumatic times, you don’t find the words. What does it mean to have a disappeared husband? How do you explain it?”

As Arpilleras became illegal, Bacic played a crucial role in protecting and distributing them through international solidarity movements. “I looked after the pieces by sending them out,” she explains. “The solidarity movement in the UK, in France, in Germany, in the United States and Canada and Japan acquired many, many Arpilleras… to support the women and give them some income for survival, but also to pass on these messages.”

Upon moving to Northern Ireland over two decades ago, Bacic found new relevance for these stories. She recalls how the exhibition “Stitching and Un-Stitching the Troubles“ led local women to recognize parallels in their own lives.

“They started to make their own,” she says. Now, the local council holds a significant number of Northern Irish Arpilleras about the Troubles.

“The Arpilleras are like ambassadors,” Bacic continues. “They tell the story of the recent history of Chile, and also they influence and encourage other cultures to tell their own stories.”

One piece that stands out is “La Cueca Sola”, the reimagined national dance of Chile, performed alone by women holding photos of disappeared loved ones. “They have transformed that message, and they have gone into the black and white to show the mourning,” Bacic explains the women state: “I don’t have my partner, now I don’t have my son with whom to dance. So I dance alone.”

Another memorable Arpillera, “No nos matarán la esperanza” (They won’t kill our hope), embodies defiance. “It’s a little piece that is very elaborate,” Bacic notes. “Don’t lose hope. Because if you lose hope you won’t take action.”

Each Arpillera is made with great intention, stitch by stitch. “You have to be very determined,” Bacic says. “It’s this stitch in and out, in and out. It doesn’t run through the sewing machine.” The process is not just physical, but emotional and temporal: “It has what I call a bank of time,” she continues. “The time of having lived experience, the time to have processed the experience, the time to decide what you tell and what you don’t tell. And the time you dedicate to making it.”

Bacic reflects deeply on the significance of the Andes in shaping Chilean identity. “Chile is over 4200km long and the Andes goes from the north to the Antarctica, and it goes from desert to the icebergs,” she explains. “It’s a determining space by which you know if we are in the north, south, east or west, it is very determinate of a physical location.” The mountains are more than geography – they are a marker of place and memory.

When her husband invited her to his mountains in Northern Ireland over 25 years ago, Bacic recalls, “I came here and I said, not laughing at him, but what mountains? Are you talking to me about Binevenagh? It’s so beautiful. But it looks a hill for me.”

Yet, she came to appreciate the distinct identity of the Irish landscape. “You have the elements with the green, the water… you come by plane and you see the green,” she says. In contrast, “You come to Chile, you cross the mountains and it’s always mountains.” Flying back to Chile, Bacic and her family always take photos of the Andes from the plane, struck by their grandeur, even in summer heat: “It always has snow on the top of the mountains.”

Her observations on the sun’s symbolism in Arpilleras are striking: “Observers would say, oh, that is the sun, the flowers, a very mild message. But no, the sun is there because it shines for everybody. The makers put the sun in because they are making what they don’t want others to experience. What has happened to me, I don’t want it to happen to others. That’s a message I pass on in the present times to the wars we have. It’s not to one or the other, it’s to everybody. The sun is there because it shines for everybody and makes no discrimination.”

Conflict Textiles has inspired communities far beyond Chile. In Catalonia, workshops led to a series on the Spanish Civil War. In Zimbabwe, women displaced and erased from official records created their own Arpilleras. “We have brought them out, emerging from silence,” Bacic says.

A particularly poignant work, by Argentinian Ana Zlatkes, depicts Bacic herself. “She did this very small piece about me, how she saw me in my action of bringing out the voices of the people who have no agency.”

Among Bacic’s collection are pieces like “No más contaminación” (No more pollution) from the 1980s, mounted on hessian to honor its origins. “The Arpilleras don’t come with the backing,” she explains. “The backing is something I invented, is like the signature of Conflict Textiles”

Bacic has carefully mounted each piece on hessian to remind viewers of the humble beginnings of the Arpilleras, originally made on sacks used for flour. “Very relevant as a few of our pieces have gone to the Tate Gallery, to the V&A and beyond.”

“In a way, it’s a frame. Also, it’s very easy to hang because we put a loop and just put a stick through and they can hang. They don’t get handled by the hand, protecting them and assuring there are no oils.”

This process ensures preservation while maintaining the character of the original textile. “I do workshops and there is no tea and biscuits; that’s very different to the average quilting bee group,” she adds. “That’s a social place. There, people can work and they can have tea before or after, but in our workshops we focus on the sewing and talk about the issues they portray.”

Another is “ Los trabajos colectivos son fuente de resistencia .” (Collective work is a source of resistance) Bacic shares, “It was a little scarf that I was given in Mexico… I turned it into an Arpillera.” The piece emphasizes that resistance can take many forms: “You can resist by working together.”

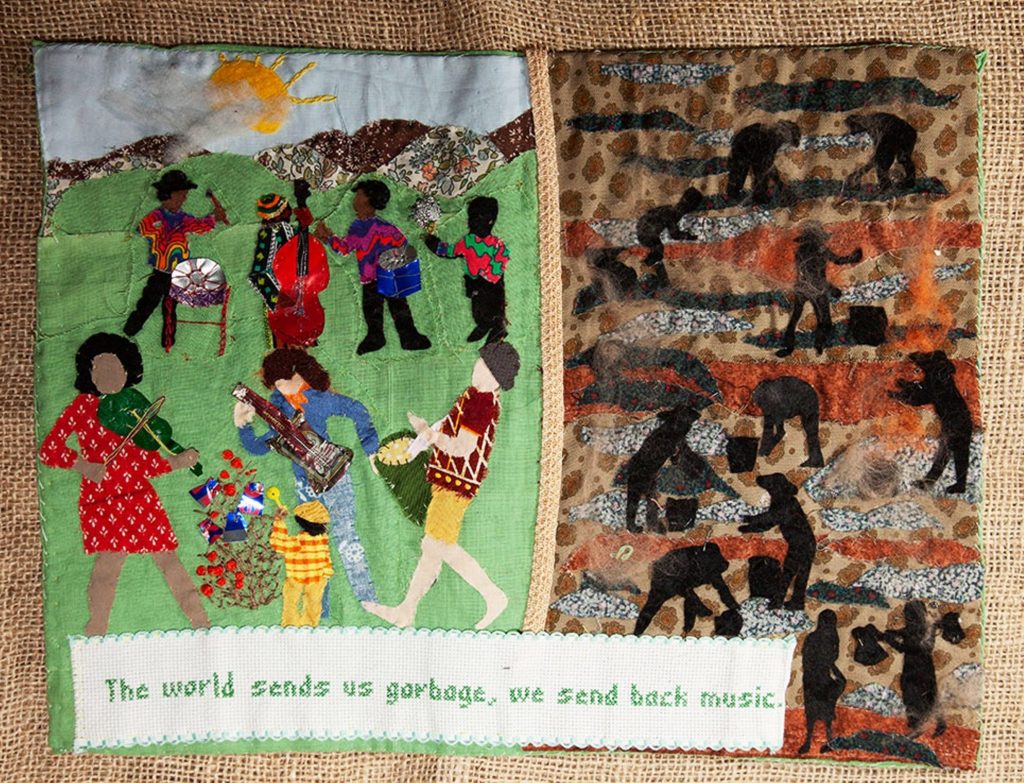

New works currently featured in the library at Queen’s University Belfast include “Landfill Orchestra,” where people in Paraguay turn rubbish into instruments that children play. The message: “The world sends us garbage. We send back music.”

Also on display is Irene MacWilliam’s “Will there be poppies, daisies and apples when I grow up?” This child-centered piece reflects environmental fears. MacWilliam received RSPB’s Artist of the Year award in 2021 for this work.

One framed scarf honors a murdered Mexican environmental defender. “This really represents us, the people, who defend nature and get killed,” Bacic explains.

“The collection started with a topic that I have worked as an academic and then as part of the Second Truth Commission in Chile,” Bacic says. That topic is the disappeared—those abducted or killed under authoritarian regimes. Her role in the Truth Commission involved documenting these stories, ensuring they were acknowledged and not forgotten.

As Bacic continued her work, she found that the themes of loss, injustice, and resistance embedded in the Arpilleras extended naturally into other global issues. The scope of the collection has since grown to include displacement and climate change. “The disappeared don’t just disappear, they’re targeted for political reasons,” she adds, emphasizing the systemic nature of erasure and how political violence continues in many forms.

Conflict Textiles continues to travel. Exhibitions have appeared in the Ulster Museum, the Basque Country, and soon in Warsaw’s National Museum of Art. Bacic will also play a significant role at a major conference in Portugal on “Slow Memory,” where she will speak at the closing ceremony on textile language and how people remember through fabric and narrative.

In addition to international exhibitions, the Conflict Textiles Collection is expanding its presence within Northern Ireland. A dedicated wall at Queen’s University Belfast’s McClay Library will host several newly curated pieces beginning May 27, focused on environmental themes and collective resilience. Among the six pieces displayed will be “Landfill Orchestra,” “Los trabajos colectivos son fuente de resistencia,” and the tribute scarf for a murdered Mexican environmental defender. These works will provide students and visitors with a tangible connection to global struggles and local reflections.

As part of Bacic’s long-term vision, parts of the collection are also displayed in the libraries at Ulster University’s campuses in Coleraine, Belfast, and Derry/Londonderry establishing textile language in the libraries. Each campus houses pieces that speak to community, memory, and activism, ensuring that students across disciplines – from law to environmental science – can engage with the textiles as living archives. “The idea is to populate with conflict textiles and textile language so that other communities take the initiative to do the same,” Bacic explains.

The Flowerfield Arts Centre event, “Community as a Superpower“ will take place on Saturday the 21st of June from 10:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. in the centre’s gardens and interior spaces. It will include exhibitions, hands-on creative workshops for children making Arpilleras on cardboard, while adult participants will craft their own textile pieces. Music, dancing, and shared stories will create a vibrant, intergenerational atmosphere. The day will be framed not as one of mourning, but as a joyful celebration of resilience, memory, and cultural expression, held in solidarity with refugees and open to the broader community.

Despite her international work, family ties remain strong. “This year for the exhibition in Flowerfield my daughter and my granddaughter are coming from Chile… my granddaughter will dance.”

”We can’t promise good weather, but we can promise good spirits and good energy.”

Find the full photographed collection of Conflict Textiles, alongside more information and upcoming events by visiting their website: cain.ulster.ac.uk/conflicttextiles

The Flowerfield exhibition “Community as a Superpower” will be available from 21st–30th June. A special Exhibition Launch will take place on Saturday 21st of June featuring workshops, music and a short talk from Roberta Bacic: flowerfield.org/events

The Latest Articles

Inni-K on Still A Day: Genuine Irish Songwriting

In the aftermath of touring Still A Day, the singer, composer, and multi-instrumentalist considers music, nature, and what remains once the movement stops.

Bob Speers and the Quiet Magic of Ireland’s Bogs

In a room filled with timber, peat, and light, artworks hung on walls are more like fragments of the land itself – weathered, breathing, and alive with memory.

Hernan Farias on Light, Connection and Creative Growth

From the Classroom to the Camera – charting his shift from teaching English in Chile to full-time photography in Northern Ireland.

The Colour & Spirit of Time: Tricia Kelly’s Journey with Ócar

Exploring how sixty million years of volcanic fire, weather, and transformation created the red ochre that now colours Tricia’s life and work.

Faith and Colour: The Genuine Art of Beverley Healy

In her imaginative work, paint becomes prayer – a meditation on trust, surrender, and creation, where colour and stillness meet to form something transcendent.

Ruairi Mooney on Creativity, Practice & the Search for Authentic Art

From the North Coast to the Canvas: a journey of resilience, daily practice, and the slow discovery of an authentic artistic voice.