Ben Ingoldsby

Cinematographer

From flax fields in Tyrone to borderlands in Mexico, Ben explores culture, vulnerability and sensorial truth – framing human connection across documentary and narrative film.

In Tyrone, the story begins with a Flax Meitheal – a community gathering organised by Fibreshed Ireland and centred on flax for the making of linen. Ben Ingoldsby was among those taking part. Although the weather prevented harvesting, the day unfolded as one of talks and shared knowledge, setting the tone for what followed.

For Ben Ingoldsby, a cinematographer working between Ireland and Mexico, these moments of shared experience carry weight. From flax fields in Tyrone to film sets across Dublin, Mexico City, and the American Midwest, his work is rooted in the intersections of culture, space, and emotion.

A Sideways Step

“My trajectory over the last couple of years has kind of taken a turn. I stepped kind of sideways, I suppose. I actually came off my bike in Mexico and slipped a disc in my neck.”

That accident forced Ingoldsby to pause his camera work and rethink his practice. “I wasn’t able to carry a camera for a bit and in the meantime, I started to get asked out on set as a camera assistant.”

The change gave him unexpected insight: working closely with other cinematographers, he was able to watch in detail how they solved problems, managed crews, and lit complex scenes. “It’s been really interesting to see how other DPs will make choices and problem solve and how they manage sets and choose to light. Usually you’re the only one doing it on set, so it was inspiring to have that kind of perspective.”

Learning From Others

“I’ve been able to be on set with people who I would have looked up to before… unofficially shadowing them. I was able to take a lot from those experiences. It’s been really, really inspiring to see – on a different scale than I would have shot previously.”

On larger productions, Ingoldsby observes the constant balancing act of cinema. “It’s all about trade-offs. You’re constantly having to deal with compromises or finding some other way of getting to the same place. That’s been really interesting to see and then to take into my own practice.”

Managing Recovery and Tools of the Trade

“I’m now at a place where I can work again… I know it’s something I’ll have to manage from now on, but thankfully I’ve been able to keep on top of it, so it hasn’t stopped me.”

He also reflects on the differences between industries. “Here in Ireland, there’s a real imperative for cinematographers to own their own camera package in a way that hasn’t been the case in Mexico or in England, where I studied. I’m now among the cost of getting my own camera package sorted. Which will give me the freedom to work how and where I want.”

Mexico as a Hub

“Mexico is really the biggest filmmaking hub in the Spanish-speaking world… by size, Mexico City is the biggest in Latin America. I was ble to get on jobs that involved both Mexico and the US. I feel really privileged to be able to witness those kinds of stories.”

Ingoldsby rejects the clichés of how Latin America is represented on screen. “You’re not in Mexico if you don’t have the sepia filter on,” he laughs. Instead, he insists that what he encounters is a shared familiarity. “It really feels that way when you’re there… the spaces are designed maybe differently, but it really feels very familiar. I think that’s just kind of responding to that truth.”

Shared Histories

The shared familiarity of space often comes through in Ingoldsby’s imagery – like an establishing shot of a wall dedicated to Catholic iconography in a family home, echoing similar walls in Ireland. It was in this context that he reflected on deeper cultural ties. “There’s a long-standing connection. Are you aware of the San Patricio’s – the Saint Patrick’s Battalion? They were a battalion of mostly Irish conscripted soldiers during the US invasion of Mexico… they abandoned the American army and joined the Mexican side. That is kind of the basis of Mexican-Irish diplomatic relations ever since.”

These threads of cultural solidarity continue to inspire him. “Being in those spaces is really special. It’s really inspiring. And it feels very familiar.”

A Personal Journey

“I studied with a lot of people from Mexico who spoke really highly of the the diverse industry there, (including my partner!), so I always had this curiosity to explore this other culture I was already absorbing.” Making that step opened up new creative ground and exposed him to different ways of seeing and telling stories.

Sensorial Truth

“For me, work on set is about being able to react to a scene from the most childlike, vulnerable place that I can put myself in. I’m always looking at how to create the conditions to get myself there. That’s something I learned through working as a documentary filmmaker – many times you’re just showing up for the first time in a new environment, and it’s all about how you react to something unfolding in real time.”

That ethos now shapes his narrative work. “I like to have that as an invitation for the viewer to participate in the image emotionally, as I’ve been participating in the scene emotionally. How can I subvert the conventional way of coverage? I’m always looking at how to subvert ending up in those kinds of situations.”

Expanding Sensorial Truth

Ben reflects more deeply on what sensorial truth means for him in practice. “As the director of the image, I see my primary responsibility as creating a window for the viewer to come into the scene and the characters’ stories as an active participant, forming their own connections and reactions to what’s unfolding before them, to tune into the humanity of the moment in the story. If that invitation isn’t created through devices of camera movement, framing, lighting and lens choice and even the length of the shot, in response to the blocking of the scene and the characters’ needs, fears, wants and desires, then I see the characters’ experience as still being untold.”

“The sensorial truth has not been externalised, the underlying emotional realism that every scene potentially has is not engaged with by me and as a consequence, the viewer and the experience is passive and in my opinion, a failure. Being in search of that is really what has informed my image-making and in turn how I work on a practical level on set, across narrative and documentary formats.”

This search also ties to his personal history. “I’m really interested in the emotional experience because of my own lived experiences and traumas, particularly around a lack of communication and having needed to approach many everyday situations in my own context through emotional analysis first. I feel the need to make a comment and communicate that through my art, and to tell stories – which is to do something my ancestors didn’t.”

“To bring that approach to the container of someone else’s story and be in service of others’ stories and ideas is a way for me to constantly keep learning and discovering different ways of seeing and understanding.”

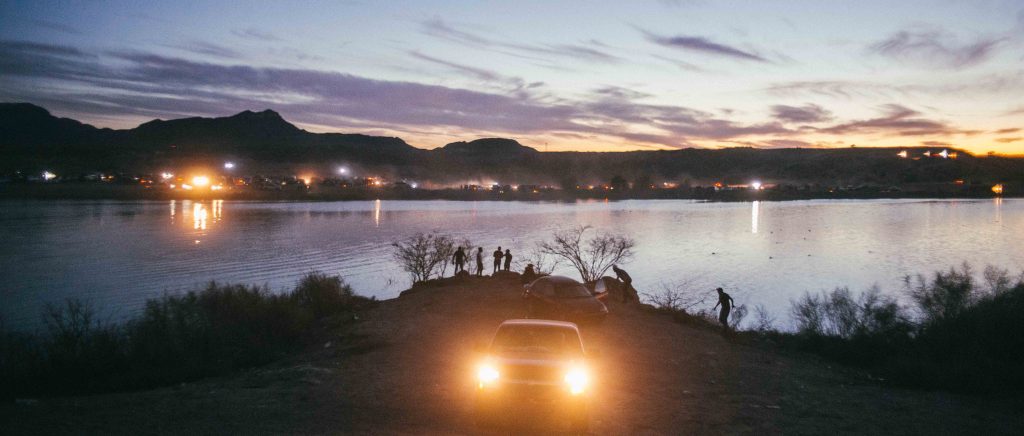

The Bridge

In 2021 Ben worked on The Bridge a short documentary – “It really started with the wedding officer, who conducts civil ceremonies all over El Paso, Texas. There’s a local statute that you can get married anywhere within the city limits, which includes half of the International Bridge. He’s been marrying people there for maybe 10 or 15 years.”

Through him, Ingoldsby and the director connected with a Mexican-American couple. “When you see a wedding in the middle of a border bridge – it’s obviously pretty unusual. But then I asked: who could this film be for? It’s a very specific local context, but it’s also universal.”

His own life gave him an anchor to the project. “I suppose I had this connection through my own experience of being in an international relationship. That meant I was really able to see myself in the story, which was really cool – because then you’re just hooked.”

Vulnerability on Screen

Using vulnerability has paid off for Ben in the moments he captures. “We were in the living room in Iowa long enough that the veneer dropped. The mum just had enough, and we were able to really see the challenges of what was going on. It wasn’t voyeuristic. It was like they hadn’t had that conversation before. By showing up with vulnerability, we triggered vulnerability in them.”

For Ingoldsby, these moments carry across formats. “I’m always kind of looking to see how can I tune in to those deeply human moments in narrative work. Is it possible to get to that kind of space?”

Returning Home

“I’m really excited to tell more stories from here, from my own community. Even before I came off my bike, I felt a longing of, oh wow, I’m doing it here so far away, but I’d love to bring myself to tell stories where I grew up.”

He cites influences like Pat Collins, director of Song of Granite and That They May Face the Rising Sun. “His storytelling really resonates with me. Stories from here, told with that kind of lyricism, are some of the most exciting to me.” Spending more of the year in Ireland feels like a new beginning. “In many ways, it feels like finding my voice allover again and I’m really excited for what that can look like.”

Find out more about Ben’s work via his website: beningoldsby.com

And keep up with him on social media: @ingoldsbyben

The Latest Articles

Inni-K on Still A Day: Genuine Irish Songwriting

In the aftermath of touring Still A Day, the singer, composer, and multi-instrumentalist considers music, nature, and what remains once the movement stops.

Bob Speers and the Quiet Magic of Ireland’s Bogs

In a room filled with timber, peat, and light, artworks hung on walls are more like fragments of the land itself – weathered, breathing, and alive with memory.

Hernan Farias on Light, Connection and Creative Growth

From the Classroom to the Camera – charting his shift from teaching English in Chile to full-time photography in Northern Ireland.

The Colour & Spirit of Time: Tricia Kelly’s Journey with Ócar

Exploring how sixty million years of volcanic fire, weather, and transformation created the red ochre that now colours Tricia’s life and work.

Faith and Colour: The Genuine Art of Beverley Healy

In her imaginative work, paint becomes prayer – a meditation on trust, surrender, and creation, where colour and stillness meet to form something transcendent.

Ruairi Mooney on Creativity, Practice & the Search for Authentic Art

From the North Coast to the Canvas: a journey of resilience, daily practice, and the slow discovery of an authentic artistic voice.